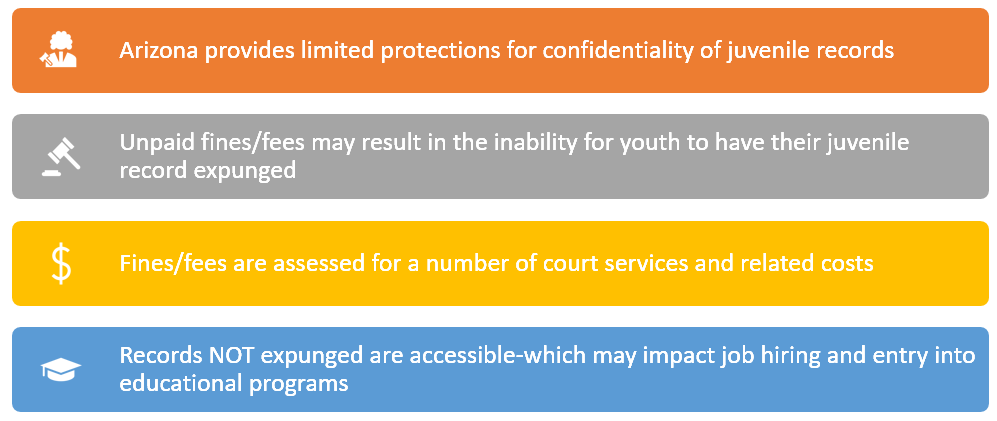

Juvenile courts in the U.S. were created to provide a separate systematized legal course for minors given that youths’ capacity for criminal action and responsibility is thought to be different, and not as liable, as that of adults. Youth are typically viewed as more amenable to rehabilitation compared to their adult counterparts and thus should be given opportunities to become successful adults. Jurisdiction over juvenile courts varies across U.S. states and territories with some juvenile courts under the jurisdiction of another court. Arizona’s juvenile court is part of Superior Court, a court that is situated in each of Arizona’s 15 counties. As in most states, the mission of Arizona’s juvenile court is to achieve public safety along with youth rehabilitation. However, at both the state and county level, some Arizona juvenile court laws, policies, and practices are not aligned with the rehabilitative aspect of its mission, and instead place undue burden on youth and their families. Two such burdens include (1) open juvenile record laws, and (2) court-related fines and fees policies. These burdens can keep youth from becoming successful adults and impede their economic livelihood, physical and mental health, and social wellbeing.

Arizona is one of seven states in which juvenile delinquency records are available to the public. To be able to have one’s juvenile record expunged or destroyed, a youth must complete probation successfully including paying restitution and all court-related fines and fees. A sizable proportion of Arizona’s court revenue comes from fines, sanctions, and forfeitures, as well as court-related fees; including from Arizona’s juvenile courts. However, such costs can be excessive and burdensome and particularly difficult for youth and families from lower socio-economic households.

Key Background Information

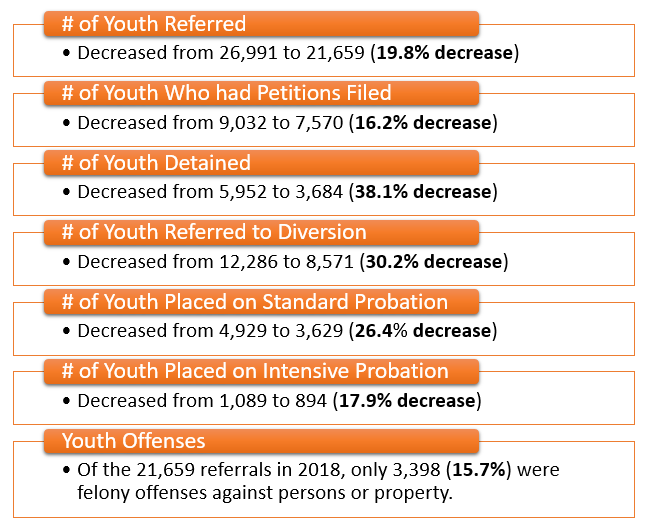

Fortunately, five-year trend data of Arizona’s justice-involved youth indicates decreases in the number of juveniles (1) referred to juvenile court, (2) having petitions filed, (3) detained, (4) referred to diversion, (5) placed on standard probation, and (6) placed on intensive probation. Along with this good news, Arizona House Bill 2055, enacted in 2019, addresses some of the burdens and other court complexities placed on youth and their families. Moreover, data from Pima County Juvenile Court (PCJC) is encouraging and shows that that the majority of PCJC-involved youth successfully complete juvenile probation.

Encouraging Arizona Trends: 2014-2018

A closer look at Pima County data indicates that some disparities exist with regard to youth who complete juvenile probation successfully. Overall, females were more successful than males, and youth who were not involved in the child welfare system were more successful than youth who were dually-involved (juvenile court and child welfare). Success based on youths’ ethnicity, age, and zip code residence varied across the five years.

Qualitative interviews with 32 court personnel across Arizona’s 15 counties addressed Arizona’s open record laws, fines and fees, and promising practices. Findings regarding Arizona’s open records law resulted in three common themes (1) the myth that juvenile records are confidential and destroyed once the youth turns 18 years of age, (2) inconsistent policies and practices within and across Arizona’s 15 counties, and (3) issues with police reports. Common burdens with regard to juvenile court fines and fees included (1) the high monetary and time-related costs of fines and fees, (2) inconsistent policies and practices within and across Arizona’s 15 counties, and (3) the encumbrances of these policies well into the youth’s adulthood. Finally, several promising practices were articulated, and included, for example, providing a destruction of juvenile record clinic, reducing detention facilities and increasing supportive youth centers, and coordinating between juvenile court and law enforcement. Across all Arizona counties, interviewees expressed the need for juvenile courts to better support youth and voiced their commitment to helping youth succeed.