Learning Opportunities for Students with Chronic Health Conditions

Learning Opportunities for Students with Chronic Health Conditions

Executive Summary

Between 20-45% of school-age children receive ongoing medical care for chronic health conditions (James et al., 2022; Stille et al., 2022; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, 2016). An estimated 13-27% of youth have a chronic physical illness or physical health-related condition (Wijlaars et al., 2016).

This study examines the policies and practices related to homebound instruction for students with chronic health conditions across the United States, with a particular focus on Arizona. The research encompasses three main aims: analyzing state policies and regulations, investigating Southern Arizona school districts' homebound instructional practices, and exploring a case study of hospital-based instruction in Southern Arizona.

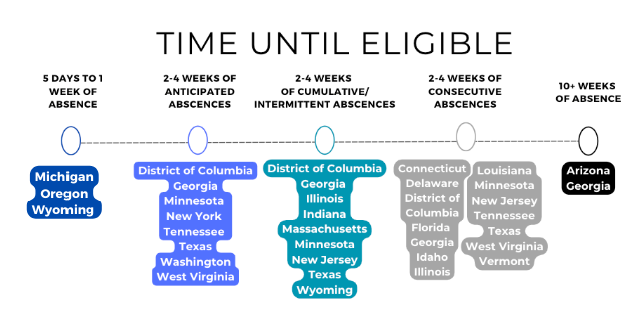

Key findings from the state policy analysis revealed that 40 out of 51 jurisdictions (including DC) have active statutes and regulations relevant to homebound instruction, with significant variations in eligibility criteria, instructional time requirements, and implementation timelines across states (Figure 1). Notably, Arizona's policy has several critical gaps, including a lengthy eligibility time frame, limited healthcare provider options, and a lack of clear implementation guidelines. The analysis of Southern Arizona school districts shows that 84.4% of analyzed districts have both homebound and chronic illness policies in place, but most adopt verbatim language from state guidelines without customization, potentially leading to inconsistent application. These policies often lack clear definitions for "timely" provision of materials and neglect critical considerations for assessments.

Figure 1: State Criteria for Eligibility Based on Time Missed

Disclosure: The criteria for eligibility based on time missed can vary between states and may depend on whether the absence is anticipated, consecutive, intermittent, or cumulative. The following map shows where states require a specific duration of absence for eligibility; however, the interpretation can differ based on the terminology used. For example, in Arizona, a student must have three school months of absences, but this can include the cumulative total of intermittent absences.

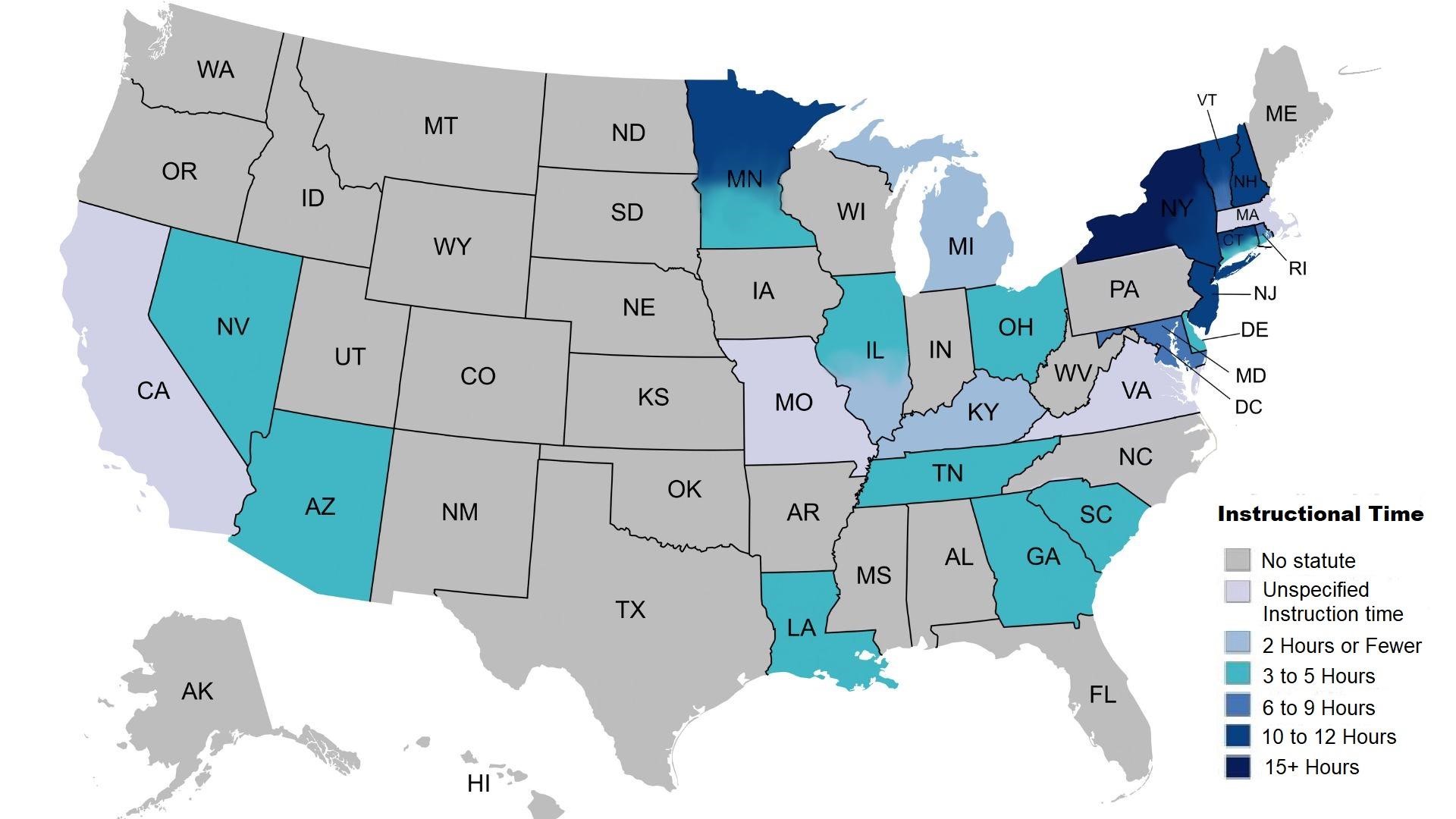

Regarding Instructional time (i.e., hours or amount of time a student who is homebound/hospitalized is entitled to), 26 (51% overall; 65% of coded states/DC) states addressed the requirements for instructional time. Requirements were coded as two or fewer hours per week (3 states) to 10 to 12 hours per week (6 states, 1 with fewer for elementary, 1 with more for secondary, and 1 based on the number of days needing service). The majority of states required between three and five hours of instruction weekly (12 states, 2 with more for secondary; 1 with less if technology is utilized). States employed different methods to calculate instructional time, including minimum hours per day, average hours per day, or a specific number of hours per week. Several states differentiated instructional time based on grade level, Four states did not specify an instructional time minimum, but rather indicated based on students' needs or as indicated in a plan developed by the teacher, school, or the Local Educational Agencies (LEA). Eleven states also explicitly deferred the specific hours based on need or the student’s Individual Educational Plan (IEP). Arizona indicates a minimum of four hours of instruction.

Figure 2: Minimum Instructional Time Requirements for Homebound Students

The hospital-based instruction case study demonstrates the potential for innovative approaches to education in medical settings, offering personalized education plans for hospitalized children while facing challenges in balancing education with medical needs, school collaboration, and maintaining student engagement. Based on these findings,

Key Recommendations Include:

- Reducing eligibility timeframes

- Expanding acceptable healthcare providers

- Establishing clear timelines for eligibility determination and service implementation

- Increasing minimum instructional time

- Developing reintegration support guidelines

- Addressing attendance tracking and curriculum requirements more explicitly

- Requiring professional development for educators

- Merging guidance on chronic health and homebound statutes

These changes would align Arizona's homebound instruction policy more closely with best practices seen in other jurisdictions, potentially improving educational access and outcomes for students requiring these services. By implementing these recommendations, policymakers and educators can better support the unique needs of students with chronic health conditions, ensuring they receive high-quality education despite health-related challenges.